The New York Times (May 25, 2021) has published an article titled “What the Tulsa Race Massacre Destroyed.”* The article is a masterful presentation of graphics that give a wonderful feeling of what Greenwood, the prosperous black neighborhood in Tulsa, was like in May of 1921. The article started out saying “The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 killed hundreds of residents, burned more than 1,250 homes…” Three paragraphs later it states that on one destroyed block “there were four hotels, two newspapers, eight doctors, seven barbers, nine restaurants and a half-dozen professional offices of real estate agents, dentists and lawyers.” That was just one block among many destroyed. The story of the destruction of life and property in the first two days of June one hundred years ago is tragic and makes one want to think “if only this did not happen, what would the back community of Tulsa accomplished?”

The article has nine authors and three pages explaining their methodology. There are 20 different sources and 14 other people listed as assisting in the production. It was a big undertaking and very impressive.

So why can’t the New York Times learn how to measure relative worth? In the fifth paragraph of the article it says: “The financial toll of the massacre is evident in the $1.8 million in property loss claims — $27 million in today’s dollars —”

This number come from one many cost of living or purchase power calculators that one finds on the internet. Except for ours, they all use the CPI to inflate a value from the past and in most cases the answers are one dimensional and misleading. In this case, the error is spectacularly bad. A quick consideration of replacement costs shows this.

For example, 27 million divided by the 1,250 homes comes out to $20,000 a home and that does not take into account all the business lost. A simple search of google asking “what is the cost of building a new hotel?” gives the following answer: “The national average range is $13 million to $32 million with most people spending around $22. 1 million on a 3-star hotel with 100 rooms.” Restaurants and office buildings might cost from $250 to $500 a square foot to build. The article says that some half a dozen churches were burned, one of the was large brick Mount Zion Baptist Church, which one can imagine would take tens of $millions to re-build today. Remember that Greenwood not only lost buildings, but also water, sewer and power utilities.

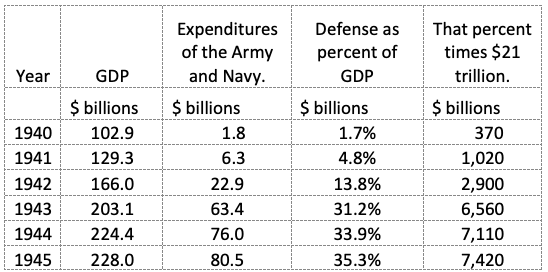

The MeasuringWorth relative worth comparator, Purchase Power Today of US Dollars, gives seven choices for the relative worth of a financial amount in the past. They range from $21 million to $534 million and are measured using price, income, household expenditures and output indexes.

There is no doubt that the output measure should be used to measure the relative value of this $1.8 million in 1921. What the comparator shows is that in 1921 the share that $1.8 million was of the GDP is the same as the share $534.06 million is of GDP today. Another way to put it is to say if we spent over $0.5 billion on restoring the Greenwood neighborhood today, it would represent the same percent of the economy’s output that was destroyed a hundred years ago.

A second best choice for the relative worth would be to use the wage measure and that would say $1.8 million in 1921 has a relative wage of $149.14 million in wages today. This can be interpreted as saying it would take this much to hire as many workers today as the $1.8 million would have hired then.

This is not the first time the New York Times has used inflation calculators to come up with very bad estimates of relative worth. Part of the blame may be search engines that lead to calculators that “adjust for inflation” simply by using the CPI and lead users to believe there is one definitive answer. Unfortunately, lots of economists do the same.

Please do not use the comment box below. You can send me an email at sam@mswth.org if you wish.

- The New York Times may not allow you to connect from the link here. The address of the article is: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/05/24/us/tulsa-race-massacre.html